Bond Basics

If you’re objective is to grow your retirement savings over time to you likely invest a significant portion of your portfolio inequities. By allocating a portion of your savings to bonds you may be able to smooth out the returns of your portfolio during market downturns.

Bonds have long been the go-to fixed income option of choice form many retirees, in fact, Bankrate.com’s list of the 9 BEST Investments for 2021 contains 3 types of bonds.

- Bond Maturity

- Callable Bonds

- Bond Coupon Rate

- Bond Prices and Interest Rates

- Types of Bonds

What is a Bond?

A bond is a loan that an investor makes to a corporation, government, federal agency or other organization. Consequently, bonds are sometimes referred to as debt securities.

Since bond issuers know you are not going to lend your hard-earned money without compensation, the issuer of the bond (the borrower) enters into a legal agreement to pay you (the bondholder) interest.

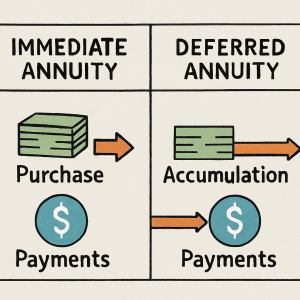

An annuity is a fixed income alternative and may be good option during below average interest rate environments, or, in a rising rate environment.

The bond issuer also agrees to repay you the original sum loaned at the bond’s maturity date, though certain conditions, such as a bond being called, may cause repayment to be made earlier.

Most bonds have a set maturity date, which is a set date when the bond must be paid back at its face value, called par value. Bonds are called fixed-income securities because many pay you interest based on a set interest rate that is specified at purchase; often called a coupon rate. Coupon Rates are set at purchase. You will likely hear the bond market referred to as the “fixed-income market.”

Bond Maturity

A bond’s term, or years to maturity, is usually set when it is issued. Bond maturities can range from one day to 100 years, but many bond maturities range from one to 30 years. Bonds are often referred to as being short-, medium- or long-term.

Generally, a bond that matures in one to three years is referred to as a short-term bond. Medium- or intermediate-term bonds are generally those that mature in four to 10 years, and long-term bonds are those with maturities greater than 10 years.

The borrower fulfills its debt obligation typically when the bond reaches its maturity date, and the final interest payment and the original sum you loaned (the principal) are paid to you.

Callable Bonds

Not all bonds reach maturity, even if you want them to. Callable bonds are common. They allow the issuer to retire a bond (buy back) before it matures. Call provisions are outlined in the bond’s prospectus (or offering statement or circular) and the indenture—both are documents that explain a bond’s terms and conditions.

While firms are not formally required to document all call provision terms on the customer’s confirmation statement, many do so. When you buy municipal securities, firms are required to provide more call information on the customer confirmation than you will see for other types of debt securities.

You usually receive some call protection for a period of the bond’s life (for example, the first three years after the bond is issued). This means that the bond cannot be called before a specified date.

After that, the bond’s issuer can redeem that bond on the predetermined call date, or a bond may be continuously callable, meaning the issuer may redeem the bond at the specified price at any time during the call period. Before you buy a bond, always check to see if the bond has a call provision and consider how that might impact your investment strategy.

Bond Coupons

A bond’s coupon is the annual interest rate paid on the issuer’s borrowed money, commonly paid out semiannually. The coupon is always tied to a bond’s face or par value, and is quoted as a percentage of par. For instance, a bond with a par value of $1,000 and an annual interest rate of 5.5 percent has a coupon rate of 5.5 percent ($55).

Many bond investors rely on a bond’s coupon as a source of income, spending the simple interest they receive.

You can also reinvest the interest, letting your interest gain interest. If the interest rate at which you reinvest your coupons is higher or lower, your total return will be more or less. Also be aware that taxes can reduce your total return.

Bonds are issued by many different entities, from the U.S. government to cities and corporations, as well as international bodies. Some bonds, such as mortgage-backed securities, can be issued by financial institutions. Thousands of bonds are issued each year, and even though bonds may share the same issuer, it is likely that each bond is unique.

The Power of Compounding

Regardless of the type of investment you select, saving regularly and reinvesting your interest income can turn even modest amounts of money into sizable investments through the remarkable power of compounding. If you save $200 a month and receive a 5 percent annual rate of return, you will have more than $82,000 in 20 years’ time.

Accrued Interest

Accrued interest is the interest that adds up (accrues) each day between coupon payments. If you sell a bond before it matures or buy a bond in the secondary market, you most likely will catch the bond between coupon payment dates.

If you’re selling, you’re entitled to the price of the bond, plus the accrued interest that the bond has earned up to the sale date. The buyer compensates you for this portion of the coupon interest, which is generally handled by adding the amount to the contract price of the bond.

Bond Prices

Bonds are generally issued in multiples of $1,000, also known as a bond’s face or par value. But a bond’s price is subject to market forces and often fluctuates above or below par. If you sell a bond before it matures, you may not receive the full principal amount of the bond and will not receive any remaining interest payments.

This is because a bond’s price is not based on the par value of the bond. Instead, the bond’s price is established in the secondary market and fluctuates. As a result, the price may be more or less than the amount of principal and the remaining interest the issuer would be required to pay you if you held the bond to maturity.

The price of a bond can be above or below its par value for many reasons, including:

- interest rate adjustments to the bond;

- whether a bond credit rating has changed;

- supply and demand;

- a change in the creditworthiness of a bond’s issuer;

- whether the bond has been called or is likely to be (or not to be) called; or,

- a change in the prevailing market interest rates.

If a bond trades above par, it is said to trade at a premium. If a bond trades below par, it is said to trade at a discount. For example, if the bond you desire to purchase has a fixed interest rate of 8 percent, and similar-quality new bonds available for sale have a fixed interest rate of 5 percent, you will likely pay more than the par amount of the bond that you intend to purchase, because you will receive more interest income than the current interest rate (5 percent) being attached to similar bonds.

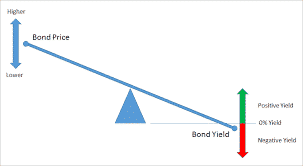

What is Relationship Between Bonds and Interest Rates?

When it comes to how interest rates affect bond prices, there are three cardinal rules:

- When interest rates rise—bond prices generally fall.

- When interest rates fall—bond prices generally rise.

- Every bond carries interest rate risk.

Interest rate changes are among the most significant factors affecting bond return.

To find out why, we need to start with the bond’s coupon. This is the interest the bond pays out. How does that original coupon rate get established? One of the key determinants is the federal funds rate, which is the prevailing interest rate that banks with excess reserves at a Federal Reserve district bank charge other banks that need overnight loans. The Fed sets a target for the federal funds rate and maintains that target interest rate by buying and selling U.S. Treasury securities.

When the Fed buys securities, bank reserves rise, and the federal funds rate tends to fall. When the Fed sells securities, bank reserves fall, and the federal funds rate tends to rise. While the Fed doesn’t directly control this rate, it effectively controls it through the buying and selling of securities.

The federal funds rate, in turn, influences interest rates throughout the country, including bond coupon rates.

Another rate that heavily influences a bond’s coupon is the Fed’s Discount Rate, which is the rate at which member banks may borrow short-term funds from a Federal Reserve Bank.

The Fed directly controls this rate. Say the Fed raises the discount rate by one-half of a percent. The next time the U.S. Treasury holds an auction for new Treasury bonds, it will quite likely price its securities to reflect the higher interest rate.

What happens to the Treasury bonds you bought a couple of months ago at the lower interest rate? They’re not as attractive. If you want to sell them, you’ll need to discount their price to a level that equals the coupon of all the new bonds just issued at the higher rate. In short, you’d have to sell your bonds at a discount.

It works the other way, too. Say you bought a $1,000 bond with a 6 percent coupon a few years ago and decided to sell it three years later to pay for a trip to visit your ailing grandfather, except now, interest rates are at 4 percent. This bond is now quite attractive compared to other bonds out there, and you would be able to sell it at a premium.

Basis Point Basics

You often hear the term basis points—bps for short (pronounced “bipps”—in connection with bonds and interest rates. A basis point is one one-hundredth of a percentage point (.01). One percent = 100 basis points. One half of 1 percent = 50 basis points. Bond traders and brokers often use basis points to state concise differences in bond yields. The Fed likes to use bps when referring to changes in the federal funds rate.

Types of Bonds

- U.S. Savings Bonds

- U.S. Treasury Securities

- Municipal Bonds

- TIPS (inflation protected securities)

- Mortgage Backed Securities

- Corporate Bonds

- International & Emerging Markets Bonds

Investing In Bonds

It’s possible to buy individual bonds or other fixed income securities but building a diversified portfolio of individual bonds takes a lot of money. What makes it difficult for individuals to buy and sell many types of fixed income securities are the high minimum investment requirements, high transaction costs and a lack of liquidity in the bond market. But it requires a significant amount of assets to build a diversified portfolio of individual bonds.

What makes it difficult for individuals to buy and sell many types of fixed income securities are the high minimum investment requirements, high transaction costs and a lack of liquidity in the bond market.

Mutual Bond Funds and Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) make it possible for everyone to invest in fixed income options. Mutual bond funds provide diversification, low costs, and experienced management teams.

- Download Smart Bond Investing (71 Pages)